Thematic Cluster: RIDS – International Relations, Defence and Security

Authors: Alek UMONT and Claire CHABREYRIE

Published date: December 20, 2025

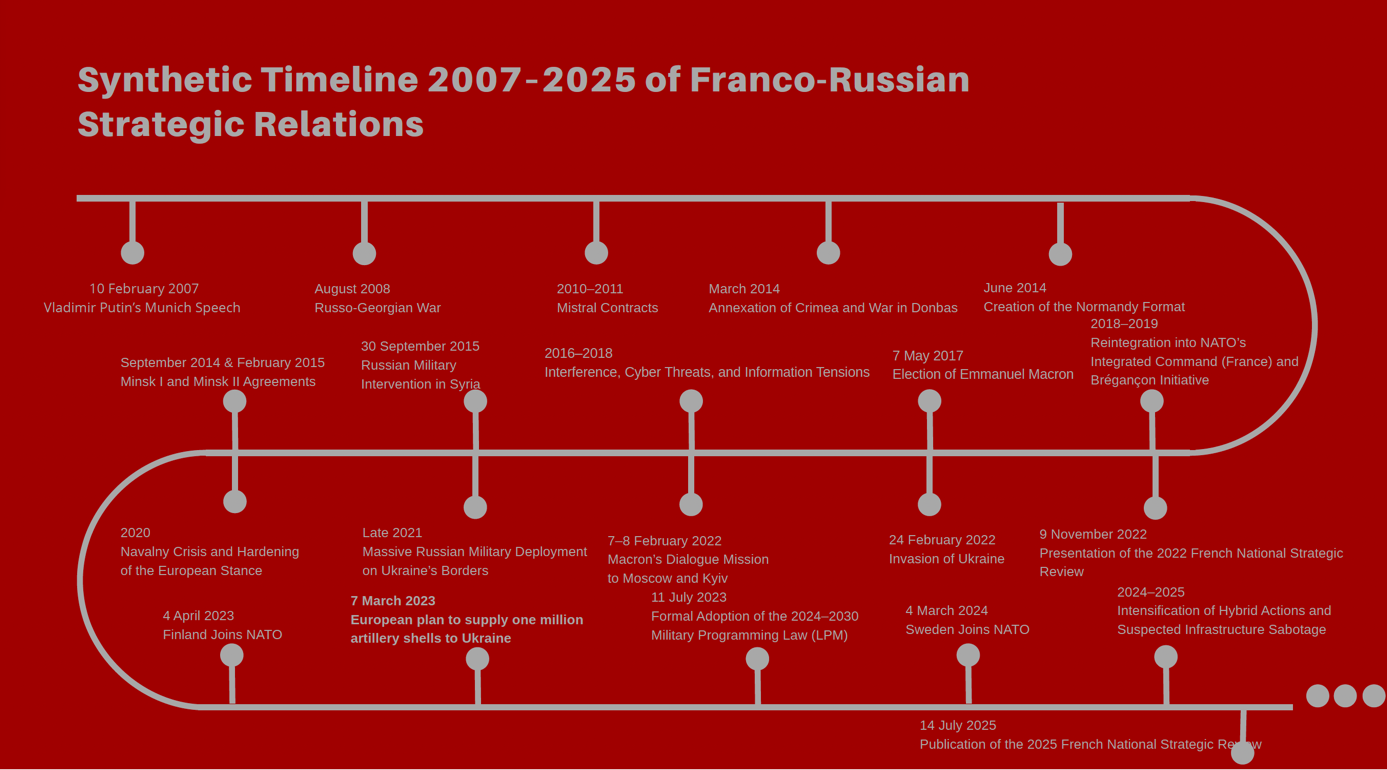

Introduction – Why this chronology?

This summary chronology accompanies the strategic note devoted to the evolution of the French perception of the Russian threat as formulated in the National Strategic Reviews (NSRs) of 2022 and 2025.

It aims to place the doctrinal shift made by France since 2022 in a long-term perspective. Far from being a cyclical or emotional reaction to the invasion of Ukraine, France’s strategic adaptation is part of a trajectory marked by an accumulation of warning signs, gradual ruptures and aborted attempts at dialogue since the end of the 2000s.

From Vladimir Putin’s speech in Munich in 2007 to the explicit recognition, in 2025, of a lasting, multidimensional and structuring Russian threat to European security, this chronology highlights the slow transformation of Russia into a coercive and revisionist power, as well as the European – and French – difficulties in drawing all the consequences in time.

This document is thus a tool for strategic contextualization, complementary to the main note:

- the note analyzes the doctrinal formalization of the threat;

- The chronology sheds light on the long time that made this formalization inevitable.

February 10, 2007 – Vladimir Putin’s speech in Munich: the founding act of Russian revisionism

Vladimir Putin’s speech at the Munich Security Conference is a true founding act of contemporary Russian strategic revisionism. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, a Russian leader is publicly and head-on challenging the Euro-Atlantic security order, denouncing NATO, American unipolarity and what he perceives as Russia’s strategic marginalization.

This discourse is not a simple rhetorical register: it announces a vision of the world based on the balance of power, absolute sovereignty and the legitimacy of coercion to defend interests deemed vital. At the time, European capitals, including Paris, still largely interpreted this speech as a posture speech, intended for an internal audience, without drawing any major doctrinal consequences.

August 2008 – Russo-Georgian War: first assumed use of force

Russia’s military intervention in Georgia marks Moscow’s first major armed operation against a sovereign state since 1991. In a few days, Russia demonstrated its ability to use conventional force to block the Euro-Atlantic anchorage of a neighbour and impose a territorial fait accompli.

For France and the European Union, the crisis is treated above all as a circumscribed regional episode. The diplomatic mediation led by the French presidency of the EU made it possible to obtain a rapid ceasefire, but at the cost of an absence of structural sanctions. This choice helps to anchor, on the Russian side, the idea that the limited use of force remains an acceptable tool in the post-Soviet space.

2010–2011 – Military cooperation and Mistral contracts: the persistence of the illusion of partnership

The signing and then confirmation of the Mistral contracts between France and Russia illustrate the persistence of a cooperative reading of Moscow. Despite Georgia, Russia is still seen as a possible strategic partner, integrated into a broader European security system.

This period reveals a lasting strategic bias: the dissociation between Russian military behavior and bilateral relations. For Paris, strategic dialogue and industrial cooperation were seen as instruments of stabilisation, whereas Moscow saw them above all as levers for international recognition and standardisation.

March 2014 – Annexation of Crimea: rupture of the European order

The annexation of Crimea constitutes a major strategic break. For the first time since the Second World War, a European border was changed by force. This gesture marks Russia’s explicit abandonment of the Helsinki principles and international law.

France condemns the annexation and supports European sanctions, but maintains a cautious approach, seeking to maintain channels of dialogue. The event is interpreted as a serious turning point, but still reversible, and not as the beginning of a lasting trajectory of confrontation.

2014–2015 – Donbass and the Minsk Agreements: Diplomacy in the Face of Coercion

The Minsk I and II agreements, negotiated within the framework of the Normandy format, reflect the French and German desire to contain the crisis through diplomacy. However, their partial implementation and repeated violation reveal a fundamental imbalance: Russia is using the negotiation as a tool to freeze the conflict, not as a political solution.

This period created a lasting strategic ambiguity: the war was very real, but kept below the threshold of full recognition, which delayed Western doctrinal adaptation.

September 2015 – Russian intervention in Syria: return of global power

The Russian military intervention in Syria marks the return of Moscow as a global military player. It demonstrates the partial modernization of Russian forces, the effectiveness of their combined employment and the ability to change the course of a conflict.

For Paris, this intervention blurs the strategic reading: Russia is both a normative adversary in Europe and a potential tactical partner against terrorism. This ambiguity contributes to delaying a unified reading of the threat.

2016–2018 – Rise of hybrid threats

The increase in cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns and electoral interference attributed to Russian actors opens up a new field of confrontation. These actions, often below the threshold of armed war, aim to weaken Western societies from within.

France is beginning to structure an institutional response, but these threats are still perceived as peripheral to traditional military issues.

2017–2019 – Attempt at strategic re-engagement under Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron’s election is accompanied by an assumed attempt at strategic re-engagement with Moscow, symbolized by the reception of Vladimir Putin at Versailles and the Brégançon discussions. The aim is to « re-anchor » Russia in a European security architecture.

This attempt failed to change Russian behaviour, but in retrospect revealed the asymmetry of intentions: where Paris sought stabilisation, Moscow pursued a strategy of gradual confrontation.

2020 – Navalny case: end of political illusions

The poisoning and subsequent imprisonment of Alexei Navalny marks a symbolic break. Russia is now fully assuming a repressive authoritarianism, including at the international level.

For France, this episode largely closes the sequence of in-depth political dialogue, without immediately leading to a complete doctrinal shift.

End of 2021 – Military build-up on Ukraine’s borders

The massive deployment of Russian forces around Ukraine is a clear strategic signal. Despite this, the hypothesis of a large-scale invasion remained disputed until the last few days, including in some European capitals.

February 24, 2022 – Invasion of Ukraine: return of the major war

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine is the definitive breaking point. High-intensity warfare is returning to Europe, putting an end to thirty years of strategic illusion.

For France, this event requires a complete review of the defence posture, political communication and military planning.

2022–2023 – Rearmament, NATO and the Eastern Flank

France is stepping up its commitment to the eastern flank, supporting Ukraine militarily and adopting an unprecedented new military programming law. NATO once again became the central framework of European security, while Finland and Sweden joined the Alliance.

2024–2025 – Lasting threat and doctrinal structuring

The National Strategic Review 2025 endorses a now stabilized reading: Russia constitutes a long-lasting, multidimensional and structuring threat. France assumes a logic of preparation for major war, integrating economy, society and strategic communication.

Overall reading

This chronology shows that the French strategic shift is neither improvised nor ideological. It is the product of a long denial, followed by a brutal but now assumed adaptation. It sheds light on the need for a posture based on duration, democratic resilience and strategic lucidity.